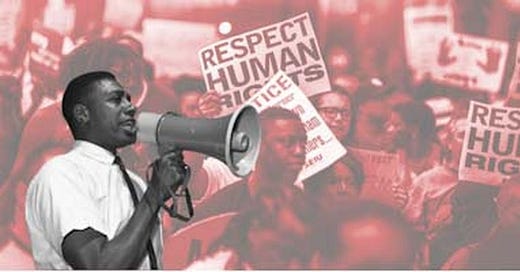

Harold Brown and the San Diego Congress of Racial Equality

A Seminal Moment in Local Black History

By Jim Miller

In recognition of Black History Month, San Diego State University honored Harold Brown last week during halftime of the Aztecs basketball game against Colorado State (Brown went to SDSU and played for the Aztecs in the 1960s).

The brief ceremony largely featured Brown’s good work promoting the academic and career success of African American students at the college with a nod to his Civil Rights Movement roots.

It was one of the great pleasures of my professional life to meet Harold Brown when my wife, Kelly Mayhew, interviewed him for our history of San Diego. Thus, Kelly and I were moved to see Mr. Brown’s life’s work prominently saluted at SDSU, and I thought it fitting to retell his story in this space during Black History Month.

Here, in a pair of small excerpts from Under the Perfect Sun: The San Diego Tourists Never See by Mike Davis, Kelly Mayhew, and me, is a pocket history of San Diego CORE and Harold Brown’s role in that groundbreaking movement in our city.

Harold Brown and San Diego Congress of Racial Equality, excerpt from Under the Perfect Sun: The San Diego Tourists Never See

“They would have you think that we are breaking the law, but I tell you that the Bank of America is the one that is breaking the law. And until Bank of America agrees to some type of conciliation with CORE, we will defy this injunction or any other injunction that they bring down. America is going to have to grapple with this, and the city of San Diego is going to have to grapple with this because this is nothing but a denial of freedom of speech of millions of Negroes, and this is nothing but a refusal to recognize the deplorable conditions of racial discrimination in this city.”

Harold Brown, Chairman of San Diego CORE

By the early 1960s, San Diego police were worried about the city's Civil Rights Movement. As former Chief Wesley Sharp remembers, "The number 1 problem started in 1964 with the passage by Congress of the civil rights legislation. Minorities thought that they had the right to do anything, and they had no respect for law and order."

Putting the unrest of the sixties into historical context Sharp claims, "CORE [Congress of Racial Equality] activity was the first indication of unrest in San Diego, starting with picketing and sit-ins. It was a troublesome time and we had no precedent, for nothing on this scale of unrest had happened in fifty-three years, not since the IWW riots in 1912." The horror with which Chief Sharp remembers CORE is indicative of the city's response to racial issues in the early sixties.

As Harold Keen's reporting pointed out in a 1963 article on "San Diego's Racial Powder Keg," there was skepticism on the part of those in local government and in the Chamber of Commerce as to whether the city even had a problem with discrimination. Leaders in the African American community saw things differently with Reverend Dwight Kyle of the Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church saying that San Diego in 1963 was "the worst place on the coast in discrimination practices . . . The powers want to whitewash the situation, make everything appear ideal. Yet we have more unemployment among Negroes [than Los Angeles or San Francisco]." The head of the San Diego National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, Hartwell Ragsdale, complained about discrimination within the labor movement as well and some of the city's harsher African American critics saw it as "a redneck cracker town where the whites view the blacks as inferior."

Along those lines, Harold Brown, leader of San Diego's CORE claimed that: "Through the years, no substantial steps were taken by the white leaders out of their own consciences. They had to be pushed and if we must hold demonstrations to obtain what is long past due, we'll demonstrate."

For many white San Diegans, this attitude, rather than discrimination was the problem. Hence Chief Sharp's disdain for protest, like that of earlier generations of conservative white San Diegans, grew out of a sense that people of color and poor people of San Diego were causing problems where none existed rather than responding to injustice.

CORE persisted in the face of opposition, picketing outside of the El Cortez Hotel while the California Real Estate Association was inside devising ways to fight the Rumsford Act and mounting a campaign against the Bank of America for their discriminatory hiring practices.

During the struggle against the Bank of America, CORE activists defied an injunction limiting picketing outside the Bank of America in downtown on Broadway. As Brown, an ex-Aztec basketball star and then junior high-school teacher, put it, "An injunction that limits to minimal expression of any group working for the betterment of minorities is immoral because it makes this group’s expression unheard."

Brown and future City Councilman George Stevens were arrested, as was Grossmont College Dean Charles Collins. Mayor Curran, members of the City Council, Judges, and police all condemned the protestors.

Collins’ jailors made their racism readily apparent, calling the white academic a "nigger lover" and asking him if he'd like his daughters to "marry a couple of niggers." Nonetheless, protests continued and the Bank of America began to hire more African American employees.

Excerpt from Kelly Mayhew’s Interview with Harold Brown in Under the Perfect Sun: The San Diego Tourists Never See:

We fought to have Blacks and other people of color work as tellers in banks and even to get jobs to bag groceries in stores. Those were examples of entry-level things that were not open, much less than the higher positions in those areas. So those conditions were really poor. Now those things are open.

Another example of how closed the society was is that Blacks lived in Logan Heights, primarily, and Southeast San Diego after that—we all lived in those areas. We could not buy a home in another area nor could we rent apartments in other areas. The conditions back then were pretty much closed to Blacks—jobs, places to live, and other areas were all closed. Now it is different. You have Blacks working as a result of the work that the Civil Rights Movement and the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) did.

When I say Civil Rights Movement, I mean as a result of the Civil Rights Movement in San Diego and in the United States, around the country, but also the work that CORE did here specifically, leading all of those efforts, mostly by itself—there was no help from other Black organizations . . .

In 1961, I had been asked to help organize a CORE chapter by Jim Stone, who is now deceased. I was involved at that time with the El Cajon Open Housing Committee, and when we were working on getting whites in El Cajon to accept Blacks who wanted to live there, we circulated petitions and went door-to-door and stuff, talking to whites about it. So Jim talked to me about CORE and about helping him form a CORE chapter here. Just a handful of us organized the CORE chapter here.

One of the first things we did, if not the first, was to hold a demonstration when President Kennedy came out here to San Diego. The purpose of that demonstration was to send a message to President Kennedy that conditions in San Diego were just as poor in terms of its racial situation as they were in other places that he may have visited in America. We knew that that information would not get to him any other way, so we held a demonstration. And of course we were accused of all sorts of stuff.

Harold Keen interviewed me to explain why we were doing what we were doing. But then after that, we held a lot of demonstrations. Over the years we demonstrated against food markets—one of them was in Southeast San Diego, where we demonstrated to try to get Blacks hired there. We demonstrated against the real estate associations—the San Diego Real Estate Association and the California Real Estate Association—and against banks, San Diego Gas and Electric Company, and the Zoo, and we also held mass marches on issues.

There were some demonstrations where we challenged the separate but equal practices that were going on around the United States. Unfortunately, there was no record of all the things that we did back then. Generally, it was a protest movement that especially protested against the conditions in which Blacks were living . . .

So Blacks in San Diego had a lot of fear of what could happen to them if they protested. I think some people were content to let other people do the work and they would benefit from it—which is everywhere. Sometimes they would realize more benefits than the person actually doing the work.

I watched many people go forward in protesting inequalities; meanwhile, the ones behind them got the jobs and the political positions and all those things. None of us were going to get those positions because what we were doing wasn’t too great for those organizations. The thinking was: “Break the individuals, especially the leaders,” which was demonstrated in terms of the jail sentences that were handed out. I always got the most time because I was the leader.

For each place where we demonstrated—and we demonstrated every week—maybe I was actually arrested six to seven times, and the jail sentences came as a result of two demonstrations at SDG & E and Bank of America. The jail sentences handed out were for “trespassing.” Those were some tough times and they’re still kind of raw for me.

***

The San Diego Central Library is commemorating the 20th anniversary of the publication of Under the Perfect Sun on Monday, March 6th at 6:30 PM.

»»»»To reserve a seat click here ««««

***