New Law Aims at California’s Biggest Crime Wave

Assembly member Lorena Gonzalez’ AB 1003 offers the possibility of righting some terrible wrongs.

The institutions in our society that are supposed to inform and protect citizens from crime haven’t grasped the seriousness of wage theft. Not paying people what they’ve earned isn’t considered a big deal. Enforcement has considered a job for the guy at the desk in the back room.

Lately the media has been chock full of stories about shoplifting and (locally) catalytic converter thefts. Stories about families living in poverty because of employers stealing from workers don't fit in a world that worships the marketplace above all.

That Walgreens store in San Francisco featured in a viral cellphone video suggesting that shoplifting is running rampant is part of a company that just coughed up $4.5 million to resolve a class-action lawsuit alleging that it stole wages from thousands of its employees in California between 2010 and 2017.

For all the publicity the cellphone video got, the lawsuit settlement garnered a single 221-word story in Bloomberg Law, an industry publication.

Wage theft, which one study suggests cost minimum wage workers more than $15 billion annually, isn’t a story because it doesn’t work with a false narrative about criminal justice reform. Vastly more people are harmed through employers cooking the books and cutting corners. The cops don't have a role and people are even more reluctant to report this crime.

Judd Legum, writing at the Guardian, puts that $15 billion number and the lack of media interest into perspective:

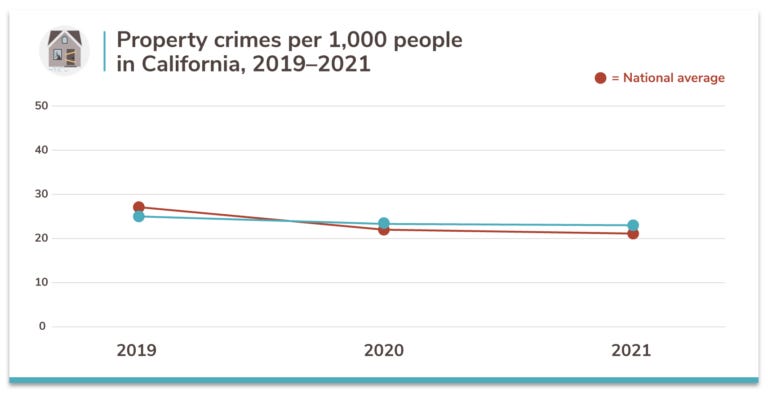

That’s more than the value of stolen goods in all property crimes, according to the latest FBI statistics.

Shoplifting is just a small fraction of total property crime because more than half of the value of all stolen property comes from stolen vehicles and currency. Nevertheless, media coverage of shoplifting vastly exceeds media coverage of wage theft. A search of United States publications in the Nexis news database reveals 11,631 stories mentioning shoplifting so far in 2021. Over the same period, the same outlets published just 2,009 stories mentioning wage theft.

The situation is bad, really bad and, like many crimes, the lower you go on the pay scale, the more people are victimized.

It’s so bad that public discussions on the topic inevitably include people who say they’ve never heard of such a thing as wage theft.

It’s so bad that California probusiness types are saying a new law giving prosecutors a path to prosecute wage thieves will drive business from the state. (Really? You have to steal? Since when?)

A terrific part of the new year (hey, I’m looking for good news wherever I can find it) is the implementation of AB 1003, Assm. Lorena Gonzalez’ bill offering the possibility of righting some terrible wrongs.

According to the Legislative Counsel, the purpose of AB 1003 is three-fold:

It makes the intentional theft of wages, including gratuities, in an amount greater than $950 from any one employee, or $2,350 in the aggregate from 2 or more employees, by an employer in any consecutive 12-month period punishable as grand theft, which under existing law is punishable either as a misdemeanor by imprisonment in a county jail for up to 1 year or as a felony by imprisonment in county jail for 16 months or 2 or 3 years, by a fine, or by a fine and imprisonment;

It specifically authorizes wages, gratuities, benefits, or other compensation subject of to prosecution under these provisions to be recovered as restitution in accordance with existing provisions of law;

It says for the purposes of the law’s provisions, independent contractors are included within the meaning of employee and hiring entities of independent contractors are included within the meaning of employer.

You’d think such a law wouldn’t be necessary, that once word got out about a scam employer, customers and job hunters would go elsewhere. But you’d be wrong.

The reality is that elements of wage theft are so common people don’t even know they’re illegal. Even when employees know they’re being ripped off, they’re unlikely to report the crime for fear of retribution or bad job references.

Many companies insert fine print into employment applications stipulating that earnings claims are subject to mandatory arbitration on a case by case basis, so lower paid workers need legal representation and can’t band together for class action lawsuits.

And when companies do get busted for wage theft, many don’t pay all the required damages. If state sanctions are on the horizon, outfits simply declare bankruptcy and reopen under a new name.

From KQED:

A landmark study of California wage claims between 2008 and 2011 found that just 17% of workers who won a Labor Commission judgment received even some of their pay. To avoid paying up, many of these employers shuttered their companies or hid assets, leaving workers nothing.

AB 1003 defines “theft of wages” as the intentional deprivation of wages, gratuities, benefits, or other compensation by unlawful means with the knowledge that the wages, gratuities, benefits, or other compensation is due to the employee under the law. (Screwing up somebody’s paycheck by accident one time isn’t considered intentional.)

The California Labor Commissioner’s office examples of wage theft include:

being paid less than minimum wage per hour

not being allowed to take meal breaks, rest breaks, and/or preventative cool-down breaks

not receiving agreed upon wages (includes overtime on commissions, piece rate, and regular wages)

owners or managers taking tips

not accruing or not allowed to use paid sick leave

failing to be reimbursed for business expenses

not being paid promised vacations or bonuses

having unauthorized deductions from paycheck

not being paid split shift premiums

bounced paychecks

not receiving final wages in a timely manner

not receiving reporting time pay

unauthorized deductions from an employee’s pay

failure to provide timely access to personnel files and payroll records

From Economic Policy Institute:

Even the theft of seemingly small amounts of time can have a large impact. Consider a full-time, minimum wage worker earning the federal minimum wage of $7.25 an hour who works just 15 minutes “off the clock” before and after their shift every day. That extra half-hour of unpaid work each day represents a loss to the worker (and a gain to the employer) of around $1,400 per year, including the overtime premiums they should have been paid. That’s nearly 10% of their annual earnings lost to their employer that can’t be used for utilities, groceries, rent, or other necessities.

If you’re interested in learning the full scope of what wage theft does to people, check out this 2021 documentation on the subject: The Ragged Edge of Rugged Individualism: Wage Theft and the Personalization of Social Harm.

In San Diego, County Supervisor Nathan Fletcher has been a driving force to make workplace justice part of the scope of the District Attorney’s office. The supes ordered staff to come up with an ordinance requiring subcontractors on development projects approved by the county to publicly disclose more information, including proof that they have workers’ compensation insurance.

Following a panel held in conjunction with the San Diego County District Attorney’s Office, Summer Stephan announced the formation of a new Workplace Justice Unit dedicated to protecting workers’ rights, prosecuting criminal wage theft cases and stopping labor trafficking.

From what I read, this new outfit looks like window dressing. The proof will be seen in whether or not more of the local offenders (typically in the construction, hospitality and janitorial industries) get busted:

The DA’s new Workplace Justice Unit is comprised of a dedicated prosecutor, DA investigator and paralegal. The Unit will prosecute unfair business practices, wage and hour violations, payroll tax evasion, wage theft and labor trafficking cases. To that end, the DA’s Insurance Fraud Division will be re-named the Insurance Fraud and Workplace Justice Division.

RESOURCES

County Workplace Justice Unit (for reporting unfair business practices, wage and hour violations, payroll tax evasion, wage theft and labor trafficking cases.)

San Diego Employee Rights Center (a non profit with services to assist victims)

Department of Industrial Relations Labor Enforcement Task Force ( Informative website explaining the laws and offering contact information for agencies willing to help workers with their claims –See Page 18 of the website pamphlet)

Hey folks! There’s a change coming to Words & Deeds real soon. I’ll be moving from WordPress to Substack, which hopefully will mean just a few changes in formatting. Stay tuned for exciting details.

Email me at WritetoDougPorter@Gmail.com