It took nearly six hours for South Korean President Yoon Suk Yeol to rescind his declaration of martial law. Legislators from across the political spectrum climbed over walls to avoid a military blockade of the National Assembly building, and, when a quorum was reached, unanimously voted to overturn the edict. In the waning hours of a bitterly cold night, tens of thousands of Koreans answered a call to show support for their legislature.

While the immediate crisis has passed, President Yoon’s future is uncertain as he has resisted calls to step down. The main opposition Democratic Party announced it would begin impeachment proceedings if Yoon did not resign immediately. The Korean Confederation of Trade Unions vowed to organize rallies and announced an indefinite strike until Yoon steps down.

So, what would a similar situation yield if it occurred in the United States, a nation with a couple centuries more experience than South Korea in democracy? The answers, based on my observations of politics in recent decades, would be disappointing for Constitutional advocates.

I say similar situations because the Constitution doesn’t expressly mention martial law. But there are plenty of ways an authoritarian-minded President could have similar results, ranging from declaring a national emergency to calling upon the provisions of the Insurrection Act. As he’s shown in the past, Donald Trump isn’t above just making shit up when it suits him.

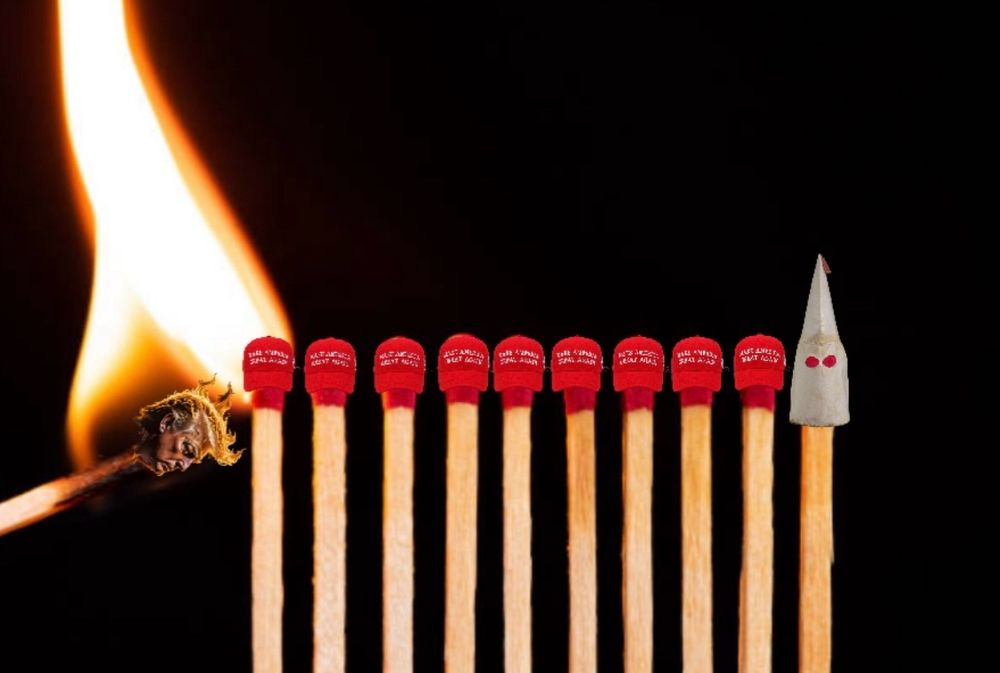

A third of the population has accepted a dystopian storyline based on threats to their safety and way of life. Another third has unplugged from public discourse, driven in part by an aversion to conflict and the overwhelming effort that it takes to keep their heads above water. And the final third is chock full of leaders unwilling to lead. An organized resistance would be stymied by Red-hatted irregulars, an inability to communicate, wannabe Rambos, and fears in the general population about retaliation.

The presently constituted Congress of the United States would fail, even if they happened to be in DC at the time. An executive branch stacked with (so far) nine billionaires in leadership positions would be scrambling to impress their Commander in Chief with their obedience. A military purged of its leadership and led by Ron DeSantis* could be counted on for support. And a Free Press, largely owned by people not likely to be impacted with consequences for tanks in the streets, would spin the takeover story to the President’s liking.

*Reports this morning are that Pete Hegseth’s nomination as Secretary of Defense will fail to garner congressional support, driven by accounts of past behavior. DeSantis has already discussed the possibility with the incoming president, according to press reports.

Do you know what ultimately gave Korean representatives, many military officers, the media, and the public the courage to defy suspension of the rule of law?

South Korea’s trade unions.

Like Donald Trump, the South Korean leader won an extremely close election following a campaign built on capitalizing real or imagined resentments. A gender divide in the electorate was a factor in driving voters. He stacked his administration with military men and intelligence officers driven by personal loyalty. He vigorously attacked the press, using judicial and civil powers, and called stories he didn’t like “fake news.” His anti-union policies failed to bolster conservative turnout in legislative districts, and were blamed for exacerbating an economic slowdown.

South Korea’s unions weren’t content to play let’s make a deal as the nation took steps toward democracy in the latter half of the 20th century. Their members were front and center in the Democratization Movement, the series of student-protests in 1980 against dictator Chun Doo-hwan.

And they have a history of coalitional organizing, seeking to address the everyday struggles of workers and their families across cultural and political boundaries.

Using their long-standing networks across the country and their connections to other civil society organizations, unions helped organize a coalition of over 1,500 organizations called the “People’s Action for the Immediate Resignation of President Park,” in the wake of a national tragedy caused by corruption and deregulation. They organized a series of candlelight protests that drew millions of participants from across the country, peaking with a day of protest in December 2016 involving roughly 2.2 million protesters, which prompted the Korean legislature to impeach the-president Park Geun-Hye.

I know that unions in the US largely supported the Harris/Walz ticket, but I doubt that most organizations’ leaders would risk being criminalized for opposing a suspension of civil liberties. And, thanks to a hostile environment for organizing and maintaining union activity, membership in the private sector has fallen to all-time lows.

Despite the Project 2025 blueprint for a Trump administration that prioritizes gutting the civil service, unions representing those workers aren’t displaying a sense of urgency. A Washington Post interview with Randy Erwin, president of the National Federation of Federal Employees, the oldest federal union, revealed the possibility of legal speed bumps to be taken in response to promised anti-worker actions.

As Hamilton Nolan and other writers have pointed out, unions are the only entities with already built infrastructure theoretically capable of sustaining effective non-electoral activism in a political crisis. Only a few leaders, like UAW President Shawn Fain, have acknowledged the challenges to democracy in our future and actually put some thought into what to do about it.

For the rest of us not connected to unions, the immediate need is building community around the expressed needs of neighborhoods, families, and groups likely to be targeted by a crackdown. Look to the often unseen actions of the Black Panther party (Free breakfast, childcare, cultural presentations) as a starting point. And understand that connections are more important than ideology at this point.

Here’s authoritarianism expert Timothy Snyder, on what we should take away from looking at the experiences in South Korea:

The most important lesson applies to all citizens. It is easy to put the responsibility on the military, the legislators, the press. But the crucial element in South Korea was the reaction of citizens themselves. This involves not just members of political parties or trade unions -- although these were very important. It was more the general sense throughout the country that this is not possible here, that we are not this kind of society, that we will have a republic and not a dictatorship. Do Americans have those reflexes?

Those instincts led South Koreans, en masse, to ignore the declaration of martial law, and to do the very things that their president tried to forbid them to do: speak, gather, resist.

Would Americans take a similar stand? Thanks to South Koreans in the last hours, and thanks to many other examples around the world, contemporary and historical, we can know the danger signs, and we can make preparations. Others have given us time to think, and have set for us good examples. We will have no excuses.

I’m going to sound like a broken record (does that even mean anything anymore?) about BlueSky, but I’m seeing a huge upside and opportunity for individuals to build their own awareness and some small sense of community in an online environment. Even if it’s only temporary, the space is available now in the face of ever-diminishing options for engagement.

Here’s a snip from historian Heather Cox Richardson on Tuesday’s events:

For the rest of the world, though, South Koreans’ immediate and aggressive response to a man trying to take away their democratic rights is an inspiration. Among other things, it illustrates that for all the claims that autocracy can react to events more quickly than democracy can, in fact autocrats are brittle. It is democracy that is determined and resilient.

The events in Seoul also cemented the shift in social media from X to Bluesky, where news was breaking faster than anywhere else, in a way that echoed what Twitter used to be. Since Twitter was a key site of democratic organizing until Elon Musk bought it and renamed it X, that shift is significant.

And finally, the events in South Korea emphasize that for all people often look to larger-than-life figures to define our nations, our history is in fact made up of regular people doing the best they can. Journalist Sarah Jeong found herself entirely unexpectedly in the middle of a coup and, recognizing that she was in a historic moment, snapped to work to do all she could to keep the rest of us informed. “I’m f*cking blasted and hanging out in the weirdest scene because history happened at a deeply inconvenient hour,” she wrote on Bluesky. “[S]o it goes.”

La Jollans Are Trying to Divorce San Diego (Again) by Jacob McWhinny at Voice of San Diego

“The main excitement around an independent La Jolla was in the fact that the more affluent and homogeneous community could finally call itself separate,” Roy wrote in an opinion piece for the Union-Tribune.

This has always been the most important idea at the heart of the secession movement, he wrote.

“It is impossible to understand the detachment proposal of La Jolla without understanding the inherently symbolic nature of such a move,” Roy wrote. “Here, as has happened throughout history, the wealthy wish to cast themselves away from the poor.”

***

What really happened after California raised its minimum wage to $20 for fast food workers by Judd Legum at Popular Information

Now, we have actual data about the impact of the law. The Shift Project took a comprehensive look at the impact that the new law had on California's fast food industry between April 2024, when the law went into effect, and June 2024. The Shift Project specializes in surveying hourly workers working for large firms. As a result, it has "large samples of covered fast food workers in California as well as comparison workers in other states and in similar industries; and of having detailed measurement of wages, hours, staffing, and other channels of adjustment."

Despite the dire warnings from the restaurant industry and some media reports, the Shift Project's study did "not find evidence that employers turned to understaffing or reduced scheduled work hours to offset the increased labor costs." Instead, "weekly work hours stayed about the same for California fast food workers, and levels of understaffing appeared to ease." Further, there was "no evidence that wage increases were accompanied by a reduction in fringe benefits… such as health or dental insurance, paid sick time, or retirement benefits."

While workers enjoyed significantly higher wages, the impact of prices was modest. A separate study by the Institute for Research on Labor and Employment (IRLE) used Uber Eats data to compare prices at fast food chains before and after the new minimum wage took effect. The IRLE study found that prices increased about 3.7% after the wage increase — or about 15 cents for a $4 hamburger.

***

Column: GOP and Musk unveil a threat to Social Security By Michael Hiltzik

You may have been tempted to believe Donald Trump when he swore, along with some of his Republican colleagues, to protect Social Security. If so, the joke may be on you.

That concern emerged Monday when Sen. Mike Lee (R-Utah) uncorked a tweet thread on X labeling Social Security "a classic bait and switch" and "an outdated, mismanaged system."

Twenty-three minutes after Lee posted the first of his tweets, it was retweeted by Elon Musk, who has been vested by Trump with a portfolio to root out inefficiencies in the government. Musk led his retweet with the comment "interesting thread"; if that wasn't an explicit endorsement, it matched his way of amplifying others' tweets, tending to give them credibility within the Musk-iverse.