The Circle of Life in Places with Unknowable Answers

I didn't become Catholic, but gained insights in a time of mourning

I recently took a few days off from writing to join our in-laws in saying goodbye to Hilda, mother of my wife, sister and brother-in-law, and a true force to be reckoned with wherever she strode.

She died on Ash Wednesday after a long illness. We brought her to San Diego three years ago after it became clear she was no longer capable of taking care of herself in her forever home, located in Abiquiu, a rural northern New Mexico census designated place, population 231.

She retired there after living and working in the Chicago area. On a visit to the area a Ginko leaf landing on her windshield became a sign that this was the place. She had no connections to anybody in the region to start with and ended up becoming a beloved pillar of the mile-high+ community.

Hilda had deep faith in Catholicism, streaming church services after she could no longer drive. She surrounded herself with symbols of her faith but wasn’t averse to learning about other relationships with a higher power.

It is hard to escape the feeling of awe and connectedness upon seeing the landscape in the region. Certainly something or someone with powers beyond human comprehension must have played a role in carving out canyons, building up towering mesas, and creating snow capped mountains visible from white sanded deserts.

Lots of artists, with Georgia O’Keefe being the most famous, have felt drawn to the raw beauty and inherent spirituality of the lands along the Chama river, a confluence of the Rio Grande running through the state from north to south.

Beyond the physical beauty of this place exists the memories imprinted through the suffering of the enslaved indigenous peoples allowed by the Spanish colonizers to settle once their usefulness (or term of labor) was ended.

From the National Museum of the American Indian:

Funded by the Spanish Crown, the Spanish first abducted and then later purchased war captives from surrounding tribes. Those “ransomed” were primarily from mixed tribal heritage, including Apache, Comanche, Kiowa, Navajo, Pawnee, and Ute. The colonists took these individuals to their households, where they were taught Spanish and converted to Catholicism. They were forced to work as household servants, tend fields, herd livestock, and serve as frontier militia to protect Spanish settlements. Many endured physical abuse, including sexual assault. The Spanish called these captives and their children “Genízaro.” The term originated from a Turkish word for slaves trained as soldiers.

This conflict and oppression affected the lives of several thousand Native people, trampling their cultural practices and spiritual beliefs.

Outside of Genízaro communities such as Abiquiú, this history has been slipping from memory. For the Genízaro people, however, it is embedded in their land and commemorated in their observances. Today, they are reasserting their Genízaro identity and culture.

On a Saturday morning in Abiquiu there was a rosary service followed by a mass at the Saint Thomas the Apostle Catholic Parish. Elements of the service, from the gardenias Fedexed from Mexico to the readings by granddaughters, were scripted by Hilda during her final months. An enchilada buffet following the service drew dozens of locals along with sizable contingents from the Midwest.

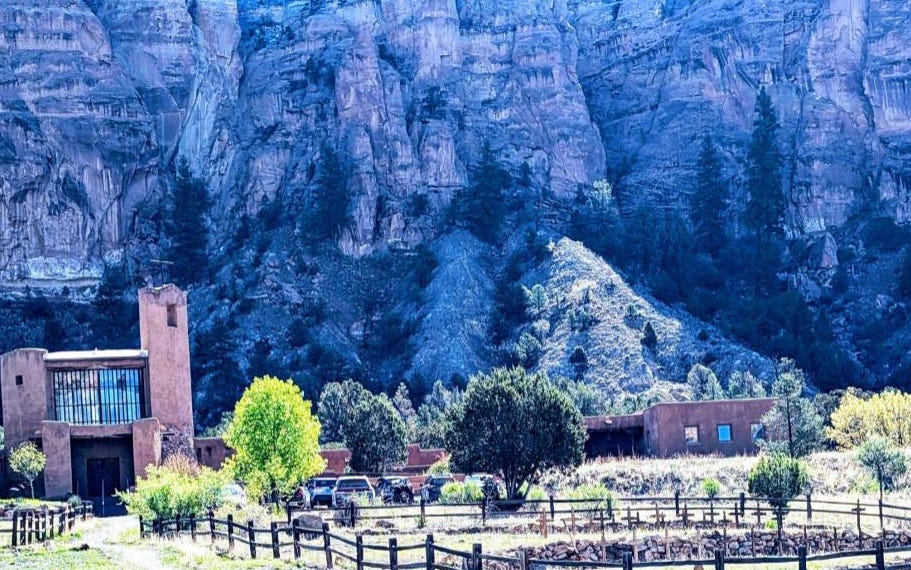

The following day, we all drove out to the Monastery of Christ in the Desert, situated thirteen miles down what at times is a harrowing road from a state highway. There, in the section of a graveyard mostly filled with deceased Benedictine Monks, Hilda’s ashes were buried in a section devoted to the faithful.

The process of saying goodbye to Hilda included other gatherings of family and friends, mostly happy experiences. She would have been proud of how her progeny pulled it off.

Now that I’ve gotten to this point, I have to admit the experience (during which I was mostly arm candy) gave rise to a level of spiritual introspection that’s long been up in the attic of my consciousness and memories.

I wasn’t “tempted” by the rituals and readings, but felt the profound sense of a community drawn together by an unknowable event in a place inhabited by powerful spirits.

Could there be something out there beyond my comprehension overseeing humanity? Did the rituals do more than placate the fears of participants of a maybe-terrible unknown? Is there a consciousness capable of existing apart from our physical being? And would this thing be capable of playing a role in the infinite spaces inside of atoms and between galaxies?

Hoo, boy; those are tough questions, and my sensibilities have long been secularized. Given the age we live in and my life experiences both physical (so far: Doug 4-Cancer 0) and spiritual (including a shit-ton of psychedelics back in the day), I’m not thinking about seeking further spiritual enlightenment. But I have learned something valuable.

I’ve gained a better understanding of the roles religion and rituals play in socialization and community, despite the fact that almost nobody actually lives up to the purported aspirations of whatever Holy Spirit they pray to.

I think it’s safe to say American culture is becoming less about church going and more about a general sense of spirituality.

I also think that those who find comfort in having their convictions drilled into them aren’t taking this trend lightly, which goes a long way toward explaining the authoritarian need to dismantle institutions that have grown up to replace or supplement the role of patriarchal organizations in managing human development and responding to threats.

An article in The New Republic explored the convictions of those who have abandoned organized religious practices:

While the circumstances of her break with the church may be unique, Bauer is among millions of people who have disaffiliated with Christian churches in the United States in recent years. According to Pew Research Center, Christian self-identification dropped from 78 percent to 62 percent between 2007 and 2024. Today, religious “nones” (those identifying themselves as atheists, agnostics, or nothing in particular) are now more prevalent, at 28 percent, than Catholics (23 percent) or evangelical Protestants (24 percent).

Reporter Sarah Stankorb interviewed Sara Moslener, a professor of American evangelicalism, religion, and sexuality at Central Michigan University:

For her forthcoming book, After Purity: Race, Sex, and Religion in White Christian America, she interviewed 65 exvangelicals. Some told her about dismantling their childhood faith and today becoming “witchy,” or “Christian but witchy,” or “Buddhist and also kind of witchy,” which for people raised with a conservative, inerrantist interpretation of the Bible is both a jump and a sign of liberation. The capacity to integrate and accept a variety of spiritual ideas is in direct contrast to the absolutism of their faith of birth.

Hamilton Nolan recently dedicated a post to exploring what “agnostic” means these days. He’s right in saying that all-too-often people who claim to be atheist are combining “the dissatisfaction of agnosticism with a determination to be rude about it.”

He makes the point that the chief demand of religion is faith. Adherents are expected to reject input from outside the realm of dogma they follow, to be blind to reality lest they step outside the social strata they inhabit.

It kinda sounds like MAGA people, doesn’t it? Except that faith is the leash used by all enclosed realities to protect itself from modernity.

Being agnostic –having questions– is not a bad thing. In fact it’s a better approach than simply ignoring the questions that the universe throws at us upon being adjacent to birth or death, when we stargaze or take in the majesty of a place like Northern New Mexico.

From Hamilton’s You Are Not Religious (Why would you be?):

Religions have great significance. They have had great impact on world history, on cultures, on wars and conquests and politics and economics. They should be studied by anyone who cares about the affairs of the world, because they influence those affairs. And they should be understood for what they are: Institutions that have grown up around popular mythologies, that derive their power from their willingness to provide answers to questions that cannot be answered, to satisfy the basic human yearning for certainty in an uncertain world. There is nothing disrespectful about saying these things out loud. It would be more disrespectful to deny them, because it would imply that there is some special class of people who are incapable of absorbing the normal building blocks of human knowledge that are available to the rest of us.

Come on, now. You may enjoy the cultural trappings of religion. You may appreciate its history, its great cathedrals, its art and poignant turns of phrase and specific moral teachings. It is fine—preferable, in fact—to feel all of these things, without declaring that you are, in fact, “religious.” Because I don’t think that you really believe all of the made-up stuff. I have too much faith in you.

I’m glad to have had these conversations with myself (which are mostly the only kind I can have, given my physical challenge). Whatever hostility I once harbored towards organized religions has been tempered by the realization of the power spirituality has to motivate us, and it’s not wise to pretend it doesn’t exist.

Beautiful essay Doug! Big hug to Hilda’s special daughter. 💙

Your insights about religion and culture deeply touch me. I am familiar with the New Mexico you write about. I was raised in the Southwest and have visited Ruidoso to visit a brother who lives there and knows something about the area of New Mexico and the rich culture of the Indigenous peoples who have inhabited this part of our nation.