The Utter Failure of Fifty Years of the War on Drugs

Short version: The government lost. Long version: A rationalization for racism and inequality, a waste of money, millions of ruined lives, and a stain on the soul of America.

On this day in 1971, President Richard Nixon declared drug abuse "public enemy number one."

Thus, the War on Drugs began. A vast infrastructure for propaganda, law enforcement, and punitory confinement was borne from that declaration.

We now know this effort wasn’t really about the use of non government sanctioned intoxicants; it was an effort to attack those the Nixon administration viewed as it’s enemies.

From an article by Dan Buam, who tracked down Nixon aide John Erlichman -the architect of the program- in the April, 2016 Atlantic:

“You want to know what this was really all about?” he asked with the bluntness of a man who, after public disgrace and a stretch in federal prison, had little left to protect. “The Nixon campaign in 1968, and the Nixon White House after that, had two enemies: the antiwar left and black people. You understand what I’m saying?

We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or blacks, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course we did.”

While the War on Drugs never succeeded in accomplishing its publicly stated rationale. While there can be disagreements about the actual numbers, the fact remains that the problem has gotten worse, not better.

It did accomplish what Nixon and his cronies set out to do. There was a nearly five-fold increase in the male incarceration rate between the early 1970s and the peak in 2008, disproportionately impacting African Americans and Latinos.

While there were other reasons for people going to jail, it’s clear the phenomena of police ‘occupying’ certain communities as part of the war on drugs was a driving force.

The nation’s prison population is declining, thanks to sentencing reforms and marijuana legalization, but, --according to the ACLU-- drug arrests account for 25% of the people locked up in the US.

Every 25 seconds, a person is arrested for possessing drugs for personal use.

https://twitter.com/ACLU/status/1405518428199436293?s=20

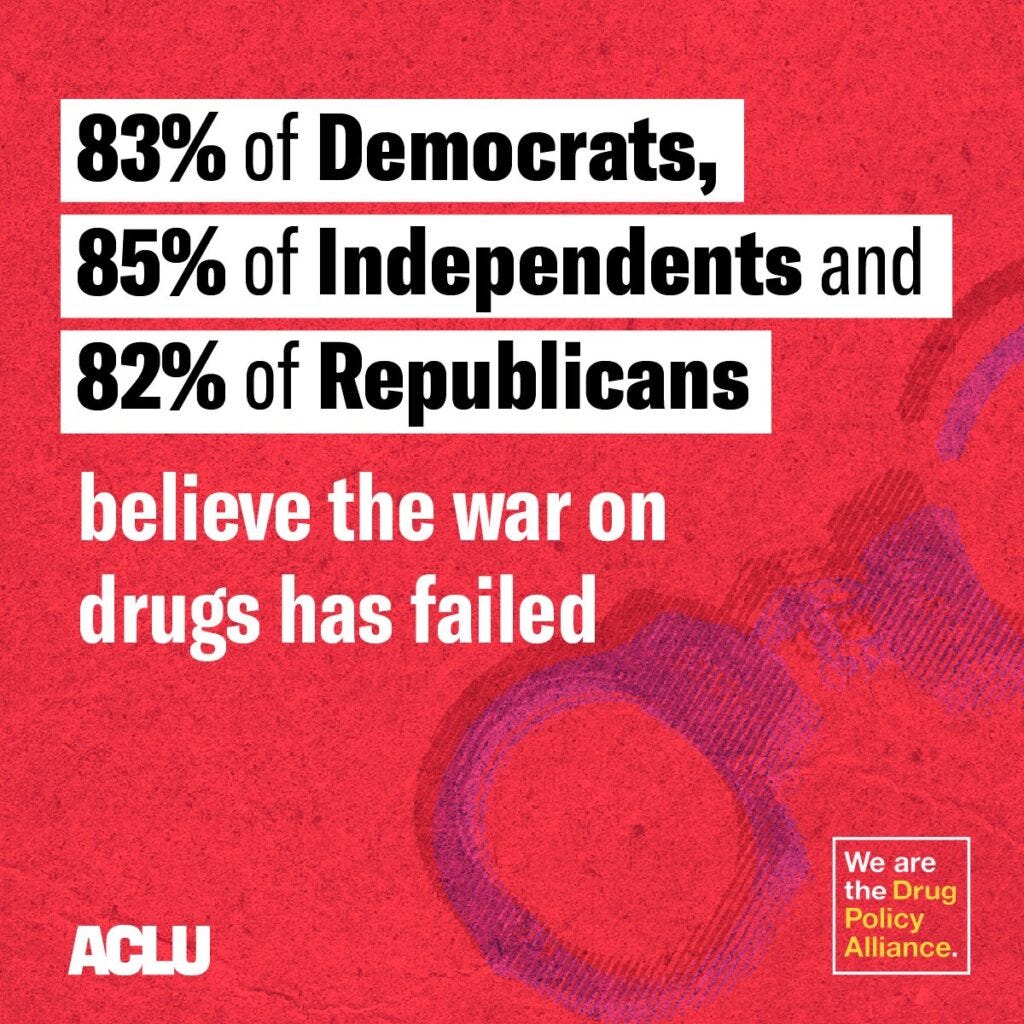

Here’s the thing; Americans know this isn’t working.

Via the Appeal:

A new national poll from Data for Progress and The Lab, a policy vertical of The Appeal, found that more than seven in ten voters (71 percent) believe that federal drug policies are not working and that there is a need for reform. Voters no longer want to treat public health issues like drug use and addiction as matters of crime and law enforcement—they support decriminalizing both drug possession (59 percent support) and the distribution of drugs in small quantities (55 percent support), while also shifting regulatory power over drugs from the Drug Enforcement Agency to the Department of Health & Human Services (60 percent support).

Representatives Bonnie Watson Coleman (D-NJ) and Cori Bush (D-MO) have introduced the Drug Policy Reform Act (DPRA). The law would eliminate incarceration as a penalty for possession of any drug, expunge possession convictions retroactively, invest in alternative harm reduction programming, and give drug classification power to the Department of Health and Human Services.

States and local jurisdictions would be incentivized to decriminalize drug possession and invest in alternatives to incarceration under provisions of the DPRA.

The mechanisms governments have traditionally used to enforce drug laws need to be retooled. Busting people for drugs is one thing that police and prosecutors are good at; other things, not so much. Less than one in five property crimes are solved. Violent crimes have fallen by half in the last 30 years, even though people perceive that more policing is needed to protect themselves. (The current "wave" of murders rarely involves random victims; it does involve the massive numbers of weapons on the streets.)

***

People aren’t going to stop using intoxicating substances anytime soon. If you look back at history, what started out as medicinal and religious uses of plants has evolved into a coping mechanism as the stresses of society have increased.

Our current societal attitudes towards drug use and abuse date back to Calvinist theologians who offered explanations for the phenomenon of compulsive drinking. They, in turn, influenced the medical profession to offer up diagnoses blaming moral weakness for what was considered sinful behavior.

At the root of all this is economics. The transactional systems created to organize societies (driven by increases in population and scarcity) have a profound influence on our physical and mental states.

We can’t simply say “take a pill” or “join a program” or “go to jail” as a solution. Our civilization needs to advance to the point where well-being means more than food on the table and/or roof over one's head. Success can no longer be simply defined in terms of acquisitions of material things.

Some variation on the concept of spirituality needs to come into play, which, speaking of drugs, is why psychedelic substances apparently have an impact on conditions like PTSD and depression. The need to “belong” is also, I think, embedded in our psyche, and it’s certainly more difficult to achieve that feeling these days.

There aren’t easy answers. But it behooves us to look at the larger questions surrounding our existence for a path forward. Not only do we have to look inward, we have to acknowledge our place in the world we live in.

Hey folks! Be sure to like/follow Words & Deeds on Facebook. If you’d like to have each post emailed to you check out the simple subscription form on the right side of the front page.

Email me at WritetoDougPorter@Gmail.com