While most of us have come to associate Labor Day with mattress sales, car deals, and/or backyard barbeques on a three-day weekend, very few people make the leap to a celebration of workers, unionism, or the American Labor movement in any way.

Actually, in the wake of the events in Chicago in 1886 at Haymarket Square, where police arrived to break up a rally in support of striking laborers pushing in part for the 8-hour day, it was May 1st or May Day that originally marked International Workers’ Day.

Unfortunately, as unions came to be associated with communism during the first and second Red Scares in the United States in the early 20th Century and onwards, Labor Day was embraced as a vanilla alternative to the more militant May Day. That’s the picture you get in the local and national media and elsewhere.

Today, more than at any time in recent history, according to a recent Gallup poll, most Americans support unions and would be eager to join one if their employer did not subvert efforts to organize, which is all too common in the corporate world.

So, when did the struggle for equality for American workers begin?

As I note in A Very Brief Outline of American Labor History for Beginners, an educational pamphlet I penned for the CFT, my statewide union:

Most labor histories begin around 1877, the year of the Great Railroad Strike that signaled the beginning of a militant upheaval of American workers bucking up against the growing inequality and oppression they faced in the midst of the American industrial revolution.

It’s important to note that any honest assessment of American labor history should start before then, however, and include the struggles of workers of all backgrounds against indentured servitude and slavery as well as the emergence of early workingman’s parties in the 1820s. One might also want to include the struggles of the emerging women’s movement that grew alongside the abolition movement and included an economic component in things like the Seneca Falls Declaration.

Unions are essentially working people standing together to form collective power in the workplace and in the political arena. Historically, unions have been the only significant institutions representing the rights of working people in America. Before unions, workers had virtually no rights in the workplace and for many years of our early history, non-property-owning men could not even vote. Thus, the history of the union movement is the history of working Americans getting together to establish some basic economic and political rights and to have a voice in American society.

The labor movement has waxed and waned throughout US history, hitting a high-water mark in the 1930s with the Wagner Act and 35-40% union density. Since then, unionization has declined in the face of repeated assaults on workers’ efforts to organize along with other internal and external barriers to union efforts. And not surprisingly, as union membership has declined, so has the middle class and economic inequality has climbed.

Moving to contemporary times, the emphasis of many existing unions on organizing as well as the legacy of Occupy and Bernie Sanders’ run for president, efforts to unionize Starbucks, Amazon, etc., and many other noteworthy developments too long to list here have occurred.

In the same CFT pamphlet above, I wrote:

As Doug Henwood notes in his review of Thomas Piketty’s seminal study, Capital in the Twenty-First Century: “The core message of this enormous and enormously important book can be delivered in a few lines: Left to its own devices, wealth inevitably tends to concentrate in capitalist economies. There is no ‘natural’ mechanism inherent in the structure of such economies for inhibiting, much less reversing, that tendency. Only crises like war and depression, or political interventions like taxation (which, to the upper classes, would be a crisis), can do the trick. And Thomas Piketty has two centuries of data to prove his point.”

The only political mechanism American workers have ever had to address this is the labor movement and that is why most Americans should care about the fate of the labor movement, whether they are in a union or not.

So the struggle continues to this day with a battle against unprecedented economic inequality and the continued bait and switch strategy of the American right, which the Democratic Party has sadly fallen prey to time and time again. This has, far too often, included a kind of backlash populism emphasis on culture wars along with Trumpmania rather than an emphasis on economic issues as they impact working people and the vast majority of Americans.

Peoples’ economic lives have been put on the back burner by many Democratic politicians, with some exceptions. Standouts include folks like Senator Bernie Sanders, Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez and others, as well as, at times, President Joe Biden.

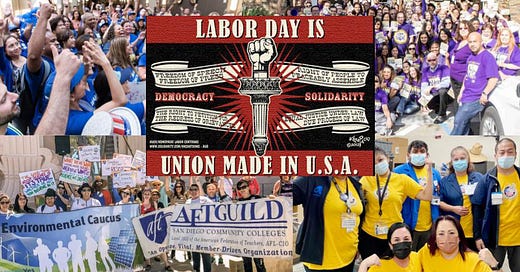

In San Diego, many in the labor movement and a number of local politicians value the continuing power of unions and their ability to help improve the lives of workers.

Larissa Dorman, currently a lead organizer for my union, the American Federation of Teachers, Local 1931, observes, “Being a unionist means combating the systems that oppress all people, standing in solidarity with the most precarious in our society and acting as an accomplice in the struggle towards liberation. The union movement has the capacity to be at the forefront of this work, however, it requires us to see our role of community building and coalition building in a different light. We sometimes forget that it's possible for our unions to act as communities of care for our membership and our community.”

As Terry Bunting, the Labor Representative from the California Nurses’ Association notes: “For me, being part of the union movement is being part of a massive wave of many different types of organizations and people from many walks of life that find a way to come together to fight for justice and fairness.”

Brigette Browning, the Secretary-Treasurer of the San Diego-Imperial Counties Labor Council makes the case that, “Being a Trade Unionist means that I always put workers first. I joined the Labor Movement because I wanted to make the American Dream become a reality for thousands of workers who have been exploited by our Capitalist Society.”

Overall, it is unquestionably true that the union movement is hugely important for the vast majority of workers unless their leadership fails to address their issues—in which case they can be voted out. So democracy, rather than autocracy, rules the labor movement, and that is a good thing.

As my recent health crisis that deeply affected my family and me illustrates, the old slogan holds: I’ve received great solidarity from the labor movement.

A special thank you to all those who reached out to me personally while I’ve been laid low, even those of you who’ve had fierce debates with me—this means more than you know (you know who you are). Taking this larger notion of solidarity going forward, I vow to be kinder.

Much love and solidarity are due not just to those folks but to all my brothers and sisters who have given my family and me so much—food, support, things we need, and most of all love. This illustrates precisely why labor matters and how it has fostered important community in ways that go beyond simple bread and butter issues.

I’ll end by inviting you to listen to what Billy Bragg sings in his new song “Rich Men Earning North of a Million,” a response to Oliver Anthony’s “Rich Men North of Richmond”:

“If you form a union, you’ll soon find/That working people are all of one kind/So we ain’t gonna punch down on those who need/A bit of understanding and some solidarity. . . Join a union/Fight for better pay/You better join a union, brother/Organize today.”

Note: More Voices of Labor columns to follow in the coming weeks.

Jim, it's great to see you back, and hopefully your health crisis is over. We're looking forward to more columns, especially now that the labor movement has some good momentum.